While we wait for the light – part 1

Top image: Black guillemot (Cepphus grylle) is often observed close to Ny-Ålesund in the polar night. This photo is from January 2014. Photo: Jan Sivert Hauglid/UNIS.

While most of us at this time are waiting for the light to return, there are many animals and algae out there that thrive in the dark. For many of the marine organisms, the moonlight which reflects the light from the sun below the horizon, and mareel (morild) are more than enough to meet their primary needs – find a partner (or two) and food!

19 February 2020

Text: Jørgen Berge (UiT The Arctic University of Norway, UNIS and NTNU), Geir Johnsen (NTNU and UNIS), Maxime Geoffroy (Memorial University, Canada), Tom Langbehn (University of Bergen and UNIS), Øystein Varpe (UNIS) and Malin Daase (UiT The Arctic University of Norway).

More than 20 years ago, the planning of the international polar year 2007-2008 began, the third major research year focusing on the polar regions (the last one was in the 1950s). One basic idea in the third polar year was that all the nations involved should provide funding for polar research projects. So also in Norway. One of the projects that was funded was led by UNIS and focused on how changes in ice cover affect light and spring bloom.

As part of the preparations for this project, instruments were launched in 2006 on the seabed in Kongsfjorden and Rijpfjorden. Due to the expected ice cover in Rijpfjorden in particular, these were launched the previous autumn and therefore made measurements throughout the polar night and winter as well. The surprises were almost in line when we began to analyze the data in 2008, and constituted for us the start of all the projects, cruises and expeditions we have carried out in the years afterwards, with the main focus on just biological processes in the polar night. In this article series we will highlight some of the new knowledge that has emerged from examples from this year’s polar night cruise with the research vessel “Helmer Hanssen”.

Today we know that polar night is a period with much biological activity. Only 10-15 years ago, we thought that the Svalbard rock ptarmigan was the only bird that overwintered on Svalbard and that virtually all organisms in the sea went into some kind of hibernation, waiting for the light to come back in the spring. This is definitely not the case! Out in the fjords around Svalbard we find both Brünnich’s guillemot, Little auks, Black-legged kittiwake, Glaucous gull and Northern fulmar. Not in the same number as in the bright part of the year, but there are no doubt a good number of seabirds overwinter in Svalbard and they also find plenty of food.

This was also clearly confirmed at Christmas in 2018 when the trawler “Northguider” ran aground in Hinlopenstretet. The trawl bag itself was left to float on the surface after the boat went aground. One of the things the coastal authority observed was Brünnich’s guillemots had become trapped in the trawl, birds that were probably attracted to both the boat lights and that suddenly there was a trawl bag of shrimp and some fish floating in the water. After the oil was removed from the ship, the removal of the trawl was therefore made a main task for the rescue crews. Important in this context is that these Brünnich’s guillemots are completely dependent on finding food all the time in order to survive – the fact that they are here is therefore proof that there is sufficient light to find and capture the food they need. . A few years ago we documented this by examining the stomach contents of some birds we were allowed to catch. It turned out that several of the birds had a lot of food in their stomachs – one of the Brünnich’s guillemots we examined had more than 200 relatively freshly caught krill in their stomachs! Whether this bird had used sunlight, moonlight, morild or city light from Ny-Ålesund as a light source, we still know very little about. But the fact that the krill appeared to have been trapped within a short window of time may be an indication that the Brünnich’s guillemot had taken advantage of the sunlight in the middle of the day to catch its prey.

The importance of light

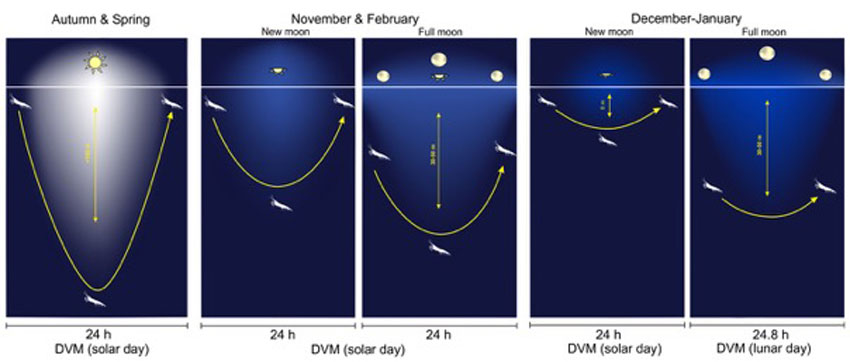

One of the most light-controlled processes is the 24-hour migration of fish and zooplankton. In all the world’s oceans, fish and zooplankton carry out migrations that extend over hundreds of meters in the water column. Up and down, every day. All year. In essence, this migration is about balancing the need to find food and not being eaten. Krill, for example, will swim in shelters of darkness and eat on plankton near the surface, while swimming down into the dark depths to hide from other predators during the day. The same goes for all the world’s oceans and many freshwater lakes. In total, therefore, 24-hour migration of fish and zooplankton constitutes the largest synchronized movement of biomass on earth. This is also the case in the Arctic. But while in most other places on earth, there is a marked difference between day and night throughout the year, the long polar night presents other challenges and migration patterns. The migration in the Arctic is, like everywhere else, controlled by light, but the natural light sources, such as sun, moon and northern lights, will vary. The sun is not always the strongest light source. In the darkest time of the polar night, it is the moon that shines brightest in the sky, causing virtually the entire community of plankton and fish to change into a lunar circadian rhythm and migration pattern. In the slightly darker months of the polar night (November and February in Isfjorden), migration will be controlled by both sun and moon: the sun gives the organisms circadian rhythm, while the moon regulates how deep they swim. Common to the entire polar night is that the migration of zooplankton and fish in the water column take place over a shorter distance when there is less light, compared to what we can observe in spring and autumn when there is a strong and clear difference between day and night.

Light is important, even for the vast majority of organisms active in the dark polar night. Those who are active in the dark usually have adjustments that allow them to see even the slightest changes in lighting conditions. Zooplankton responds at moonlight down to at least 50m depth, the faint glow of sunlight in the sky to the south controls daily migrations of both fish and zooplankton throughout the polar night, and seabirds are able to find their prey. In other words, they are able to see light at levels far below what we humans are capable of. But this also makes the same animals extremely vulnerable to light pollution. In other words, as a kind of by-product of their incredible ability to detect light, they are particularly vulnerable to artificial light from, for example, a research vessel.

The threat of light pollution

Nowadays, of course, light pollution is not a very big problem, but with a warmer climate and increased human activity in the northern areas, this could be a bigger problem in the future. And not least, while animals and algae have been exposed to changes in temperature, salinity, acidity, natural emissions of hydrocarbons and ice conditions for millions of years, light pollution is a whole new and unique phenomenon that came with the invention of the light bulb and electric light a bit over 100 years ago. Along with plastics, with large-scale production that started 50 years ago, light pollution poses entirely new challenges for organisms in the sea.

And in the otherwise dark polar night, where the moon is the strongest light source, light pollution is perhaps the threat that we will at least be able to do something about in the future. Where people travel in the dark, there will also be light. The problem is that today we know very little about how light pollution will affect the various organisms and whether it will have any effects on the ecosystem. And more importantly, the way we do marine life studies today, with large and well-lit research vessels, will most likely affect the environment around the boat in a way that provides much of the data with some, very limited value. In other words, light pollution in the polar night is not only a problem that arises when a ship, oil platform or other form of human activity lights up an otherwise dark environment, but also poses a significant challenge to the needs of both researchers and government agencies to obtain correct data.

In 2016, we conducted a pilot study in Kongsfjorden where it turned out that zooplankton down to 50m changed behavior when we used regular headlights to work from a small open boat. Light from the research vessel “Helmer Hanssen” was found in the same study to have an effect as deep as 100m. In a future warmer Arctic, with potentially increased opportunities for polar night fishing, it will be important to be able to monitor and determine the amount and extent of harvestable species. If such measurements are made from ships with lighting when it is dark, there is a high probability that these will not be correct! This theme is central to a new large research project funded by the Research Council of Norway, where over the next five years we will study and quantify the effect of light pollution on both organisms and our own measurements.