Teamwork makes dream work

Deploying a light sensor on Van Keulenfjorden. Photo: Janne Søreide/UNIS

Top image: Professor in Arctic Marine Biology, Janne Søreide shows Sunniva Sørby how to deploy a light sensor. The sea ice lasted for only 14 days. At the end of March a storm hit and broke up the ice. Luckily the Hearts in the ice-team managed to save the light sensor deployed.

27 May 2021

Text: Maria Philippa Rossi

Science research and fieldwork is often time consuming and expensive to carry out. On Svalbard, two citizen scientists overwintering in an old trappers’ cabin in Van Keulenfjorden have aided UNIS researcher by collecting ice core samples.

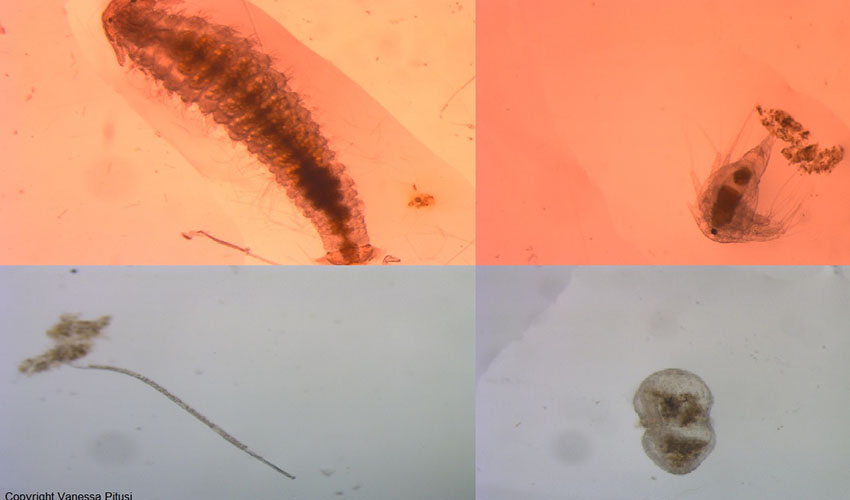

Rebecca Duncan and Vanessa Pitusi are two PhD-students at UNIS doing research on ice algae and meiofauna. This is a highly understudied topic, and researchers know little about these microscopic organisms living inside the sea ice.

Hilde Fålun Strøm and Sunniva Sørby, two women who have overwintered in the Arctic since 2019, have this year aided the PhDs’ research.

Women with passion for the Arctic

Strøm and Sørby initiated the project “Hearts in the ice” as they began a 9-month overwintering project in September 2019. They were the first women in history to overwinter in Svalbard without men. Their project promotes global dialogue about the changes they experience in the polar regions, and focus on issues relating to female leadership, STEMM, sustainability and innovation. Due to Covid-19 they decided on a second overwintering that they completed in May 2021.

– We visited Hilde and Sunniva in March and got to see how they’ve been living for the past year and a half. We checked out the ice conditions together, taught them how to take ice cores and the associated measurements like snow depth and sea ice thickness. They were then able to take regular cores for UNIS, Duncan explains.

Duncan studies the microscopic ice algae that grow inside sea ice. These highly specialised ice algae can grow almost without light. The ice algae can bloom up to two months earlier than phytoplankton in the water column below. This makes ice algae a critical early food source for many Arctic marine invertebrates, giving them a head start on reproduction and growth.

– The ice algae are the bottom of the marine food web. How their protein lipid and carbohydrate content changes will carry through the ecosystem impacting the higher levels, such as fish, seals and polar bears. In fact, polar bears can derive up to 70 per cent of their lipid content indirectly from sea ice algae sources. So, whilst sea algae might not be cute and cuddly, they really do matter, Duncan says.

Extensive sampling to get required data

At each sampling station the researchers measure the light penetration under the ice. The sampling is time consuming and getting to the sampling site often takes hours each way.

– The sampling is extensive and getting to the sampling sites means 2-3-hours’ drive via snowmobile. Not only is it time-consuming, but it is also expensive and dependent on snow- and ice conditions. It also increases the carbon footprint of our research. Having Hearts in the ice collecting cores from outside Bamsebu we have been able to increase our capture of the seasonality of the ice ecosystem without increasing our logistical effort and environmental footprint, Pitusi says.

Pitusi’s work is to look at how the seasonal changes affect the life in the sea ice. One of the things she is trying to find more information about is what environmental factors shape meiofaunal communities and what critters are using the ice, in Svalbard. She explains that the sea ice looks like a Swiss cheese, with lots of holes and there’s flora and fauna within.

A nursery for bottom species

The sea ice habitat is an important nursery ground for some bottom species. Here their larvae can hide in the small brine channels and feed on ice algae – safe from larger predators which cannot access the sea ice due to their too large body sizes.

– In Svalbard this topic is highly understudied, and the collaboration with Hearts in the ice has made it possible to further map the changing sea ice conditions. It’s important information UNIS needs to map the changes of the sea ice conditions and marine ecosystems more accurately, Pitusi says.

Losing sea ice is challenging, as researchers yet don’t know how important these microscopic beings are for the remaining food chain in the Arctic.

– We’ve been grateful for the collaboration with Hearts in the ice. As Arctic explorers and adventurers, Hilde and Sunniva are passionate about understanding what’s happening in the Arctic and how climate change is affecting it. As scientists, we’re also passionate about exploring and understanding, Duncan says.

– We’re using our independent skill sets to not only do the science and the research, but to spread these messages to the public.

More information:

Video about the UNIS/Hearts in the ice-collaboration

Hearts in the ice on web, Facebook or Instagram.