Let’s talk dirty

Arunima Sen is a postdoc in the Benthic Ecology group at Nord University and soon-to-be associate professor at UNIS. She has two primary research agendas : sub-Arctic fjord ecology, and carbon and nutrient cycling in the high Arctic. She is also a part of the Nansen Legacy research project, and this blog is from a cruise in spring 2021.

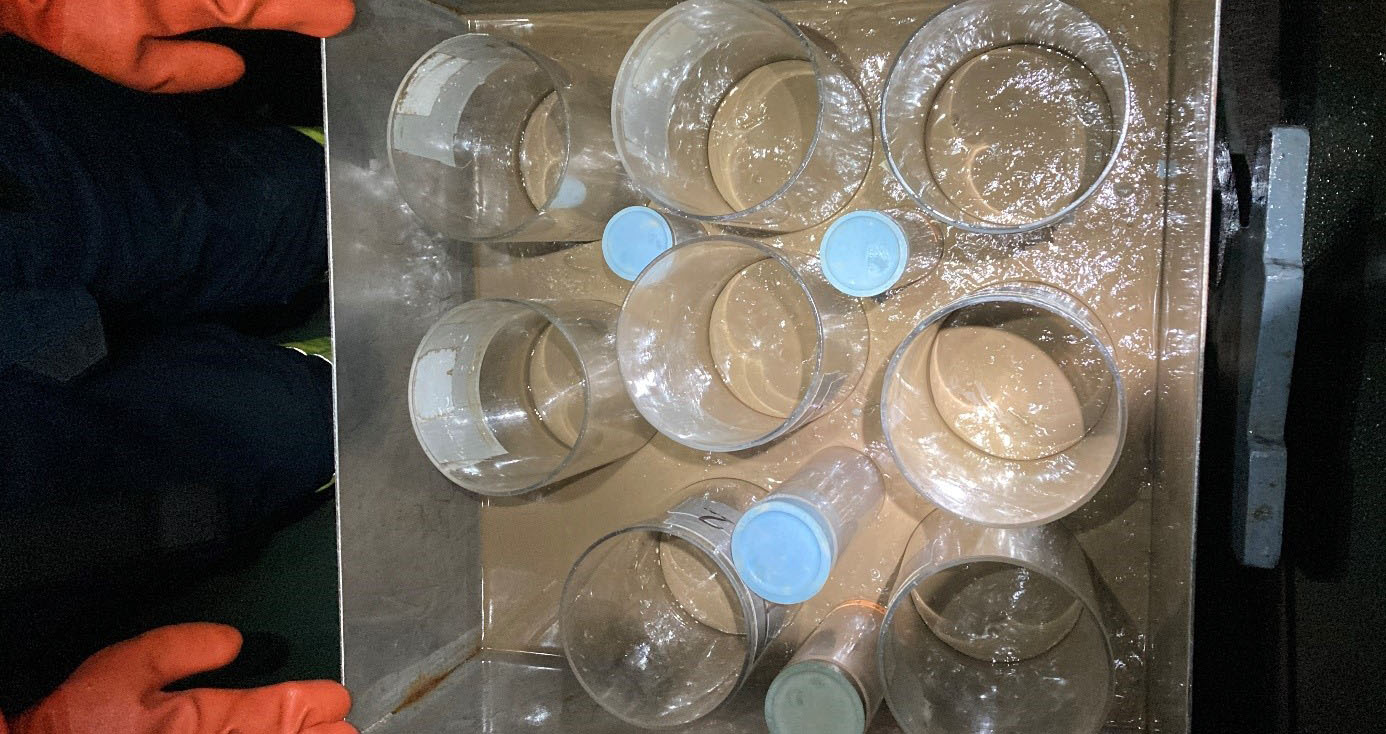

Some of the benthos team labelling and preparing samples before they get muddy. Photo: Eric Jorda Molina

Text: Arunima Sen

Water, water everywhere on this blue planet. But there is also a dirtier side to the sea, because under the waves is solid (though often muddy) ground. Even dirt from land eventually reaches and lays to rest on the seafloor. The ground beneath the sea is in fact, critical for maintaining a healthy planet. Most people don’t realize that since nature documentaries are literally more wishy washy in their focus. Plus, I admit, mud, dirt and grime are not particularly charismatic.

Even my colleagues on board are terrified of setting foot into my lab or being on deck when seafloor sampling is taking place. But if you are willing to get your hands dirty, a whole new world opens up. The seabed and the animals living there are collectively called, the benthos and it is one of the largest and most diverse habitats on the planet.

Dinner plate and carbon reservoir

Food is literally dirt cheap since a common feeding strategy of benthic animals is gobbling up dirt and sustaining themselves on the organic material rolled up within the dirt. Other animals filter water and eat whatever gets stuck on their biological sieves. Similar to life on land, benthic animals crawl or walk on the surface of the seafloor, or burrow into tunnels. This takes carbon from the surface of the seafloor to deeper in the sediment. That carbon is then safe from getting washed away by every passing current, so it gets stored and sequestered under (marine) ground.

At the global scale, this has a huge effect. The seabed is where carbon goes to die and remain locked away, which takes it out of the atmosphere. In fact, the deep ocean is the biggest reservoir of carbon in the world. In other words, all those dirty little animals are critical for maintaining carbon budgets and preventing runaway greenhouse effects. So even if the Nansen Legacy ‘s benthos team and I have a dirty job, there is a method to our muddiness. And in the end, we get the dirt on everyone else’s study subjects.

Research on board

As part of the Nansen Legacy project, we are looking into the variety of benthic animals in the Barents Sea, from shallow shelves, to deep basins. No animal is an island, so we also conduct experiments to capture some of the effects the benthos has on the rest of ocean life. Every breath the benthos takes releases carbon dioxide – no different from us, but this is the critical compound that gets converted into food at the sea’s surface, in the presence of light.

On the ship, we maintain the cold and dark conditions of the deep and literally measure the pulse of the seafloor to quantify this relationship between seafloor and sea surface. Since life and especially the Arctic is not static, we also conduct these experiments imitating future scenarios, such as with warmer temperatures. Therefore, our end-goal is to understand details of the Arctic benthos and its sphere of influence across both time and space.